|

If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

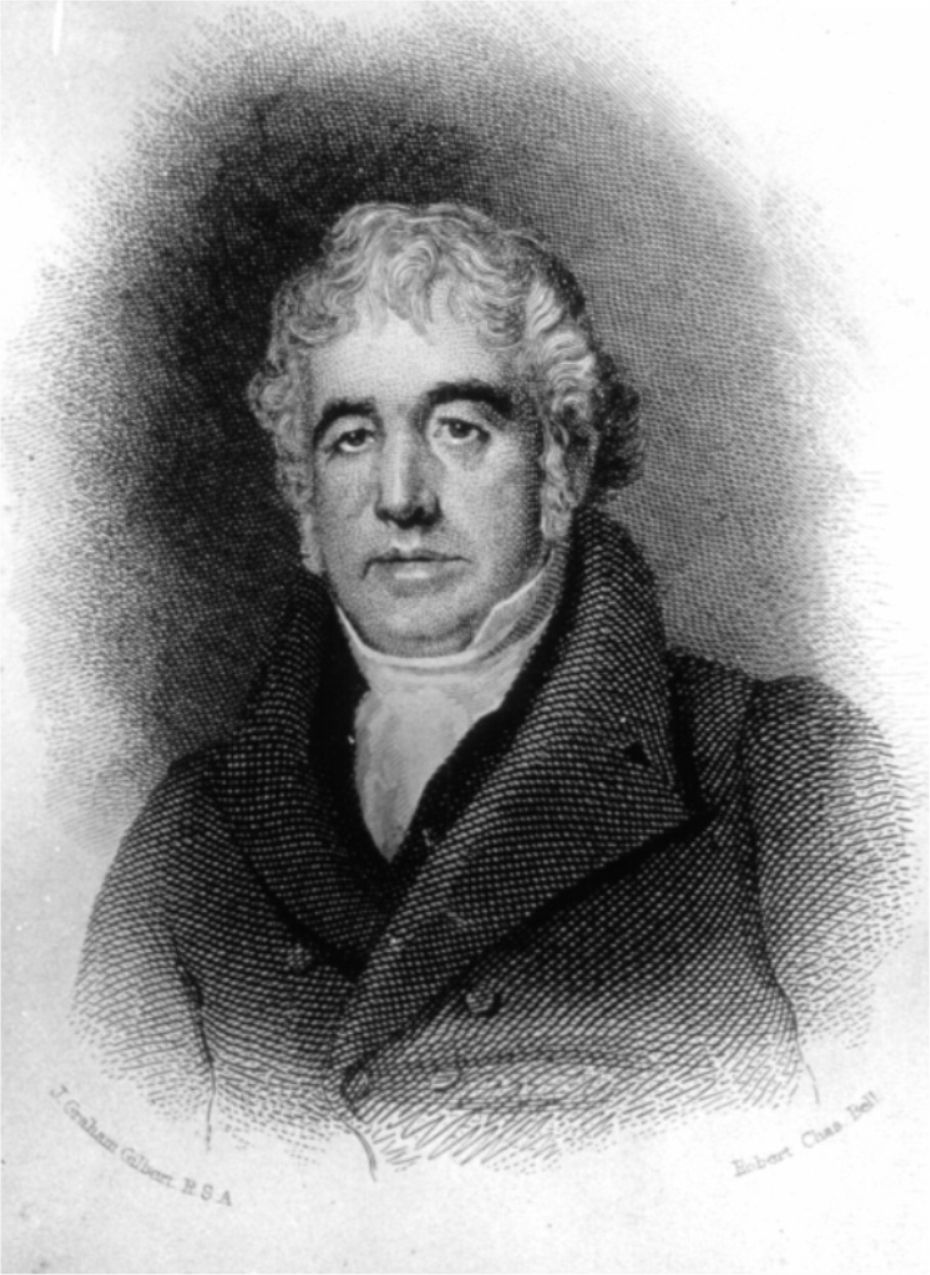

Charles Macintosh and Co. The History of the Company

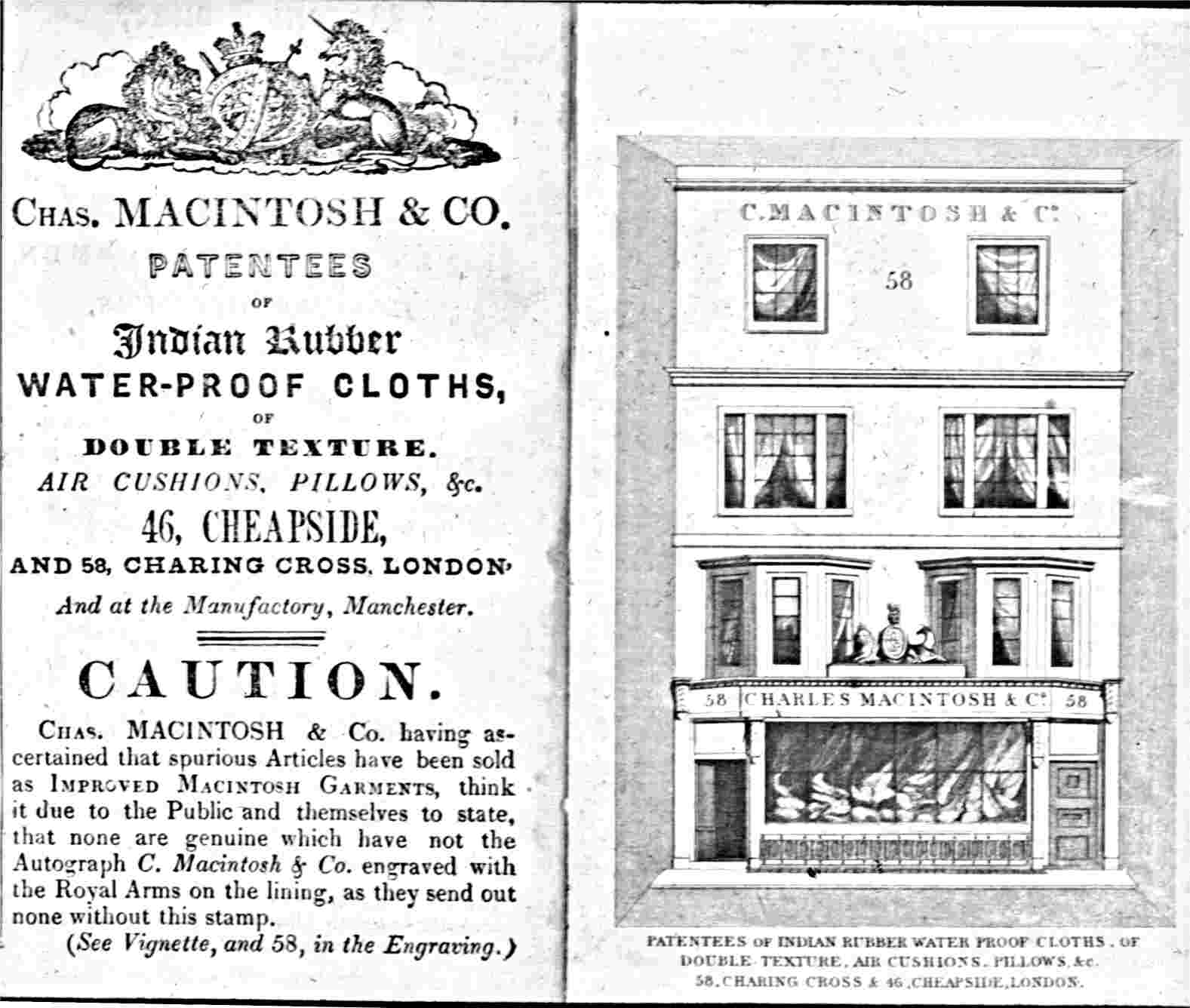

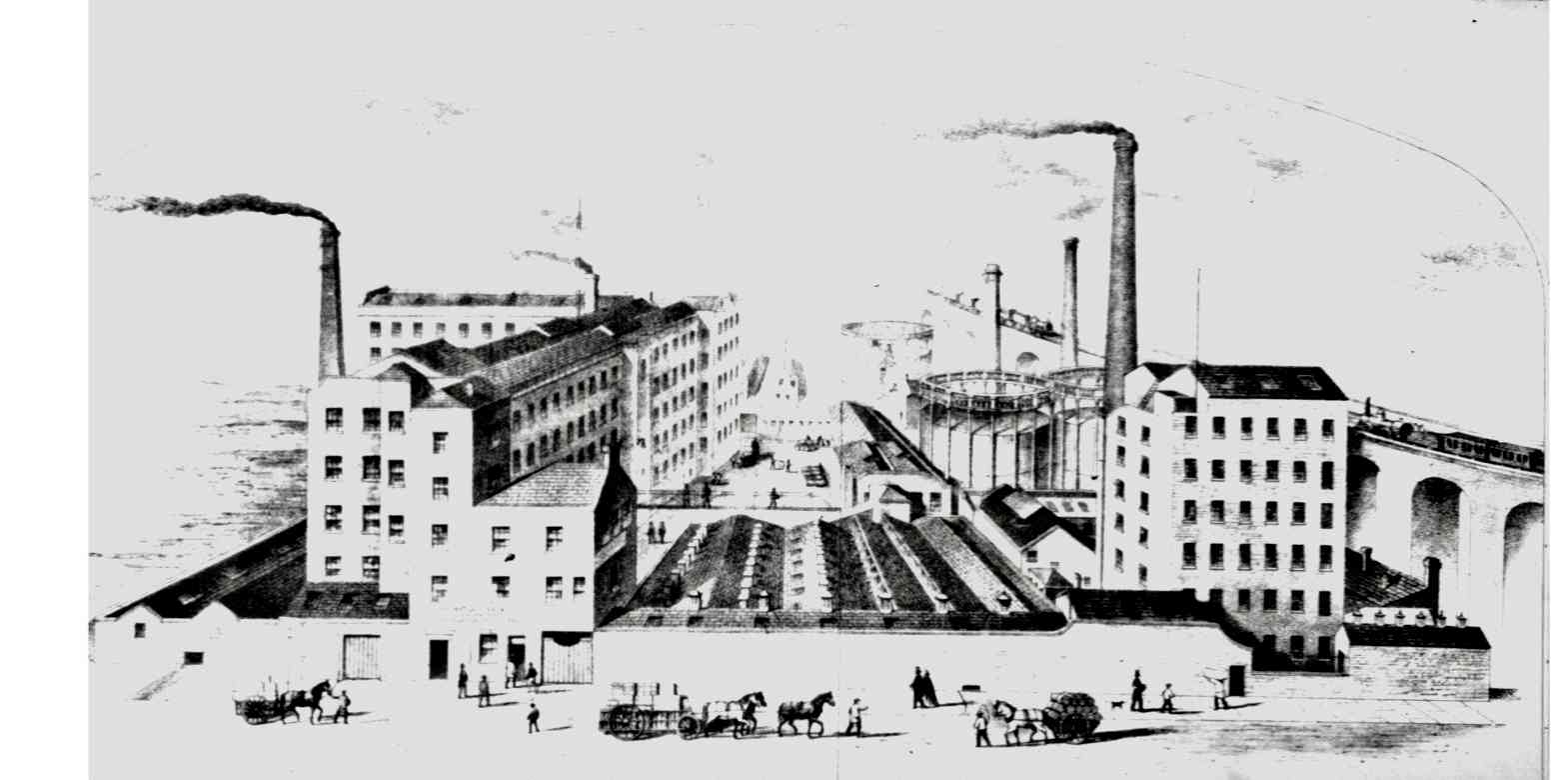

Charles Macintosh is known internationally as the inventor of the (almost) eponymous mackintosh raincoat which he developed between 1823 and his death in 1843. He was born in Glasgow on December 29th 1766. His father owned a dyeing business but the young Charles initially went his own way, opening the first alum works in Scotland in 1797 and, with Charles Tennant, developing a dry bleach made from chlorine and slaked lime. This made him a considerable fortune and enabled him to research into various other fields of chemistry. By 1792 Glasgow had begun to introduce gas lighting into the streets, as well as a few prestigious properties, and in 1817 the Glasgow Gas Light Company was formed. The gas was produced from coal and Macintosh contracted to buy the waste products as he could extract ammonia from them which, in turn, could be used by his father’s company to make the violet-red dye cudbear. He was still left with a further waste material – a mix of organic liquids called collectively coal tar naphtha. As early as 1791 Fabrioni had remarked on the excellent solvent properties of this for rubber but he seems to have been ignored and it was not until 1818 that J Syme proposed that “a substance from coal tar” could be used as a rubber solvent – and noted that it was cheap and readily available with the new gas lighting. The practice of coating cloth with rubber latex to render it waterproof had been known to the South American natives for many hundreds of years but latex was too unstable to be shipped to Europe so the industry had been waiting for just such a discovery. Macintosh began experimenting with this material as solvent and found that the resulting fabric was waterproof - although it was also sticky and had a foul smell. His brilliant idea to avoid the stickiness was simply to press two sheets of fabric together with the rubber sandwiched between them. This he patented in 1823 thereby bequeathing his name to posterity. Unfortunately the smell remained! In 1824 Macintosh persuaded the Birley brothers, cotton spinners and weavers of Manchester, to build a factory next to their mill in which he could manufacture his rubberized cotton. However, he encountered numerous problems, not least the smell, and his cloth was shunned by society although there was a large and steady demand from the armed forces and merchant navy. I should imagine that the waterproofing properties more than compensated for one extra smell amongst many the soldiers and sailors would be experiencing! Macintosh was punctilious about replacing unsatisfactory products, or giving cash refunds, and ten years down the line the factory was still not making money. It was time for the ‘father of the UK rubber industry’ – Thomas Hancock – to ride to the rescue. In 1820 he had built a machine (his ‘pickle’) to tear up scrap rubber in the hope that the freshly torn surfaces would fuse together to give a uniform block which could then be re-used. The process worked to perfection with the unexpected benefit that the torn, or masticated, rubber was much more soluble in his preferred solvent, a mix of oil of turpentine and naphtha, than was raw rubber. He was aware of Macintosh’s work and in 1825 he took out a licence to manufacture the patented “waterproof double textures”. Hancock’s solutions were able to have a higher rubber content than those of Macintosh and so could more readily give a uniform film on the cloth with less penetration through it and with less odour. Hancock quickly realized that his products were significantly superior to those of Macintosh, and eventually, with much reserved secrecy on both sides, they co-operated, although remaining separate corporate entities, to improve their products. Mutual trust slowly developed and in 1831 Thomas became a partner in Chas. Macintosh & Co., their two companies merged and two years later the combined company bought Thomas’ brother’s specialist rubber business which manufactured a range of rubber medical devices.

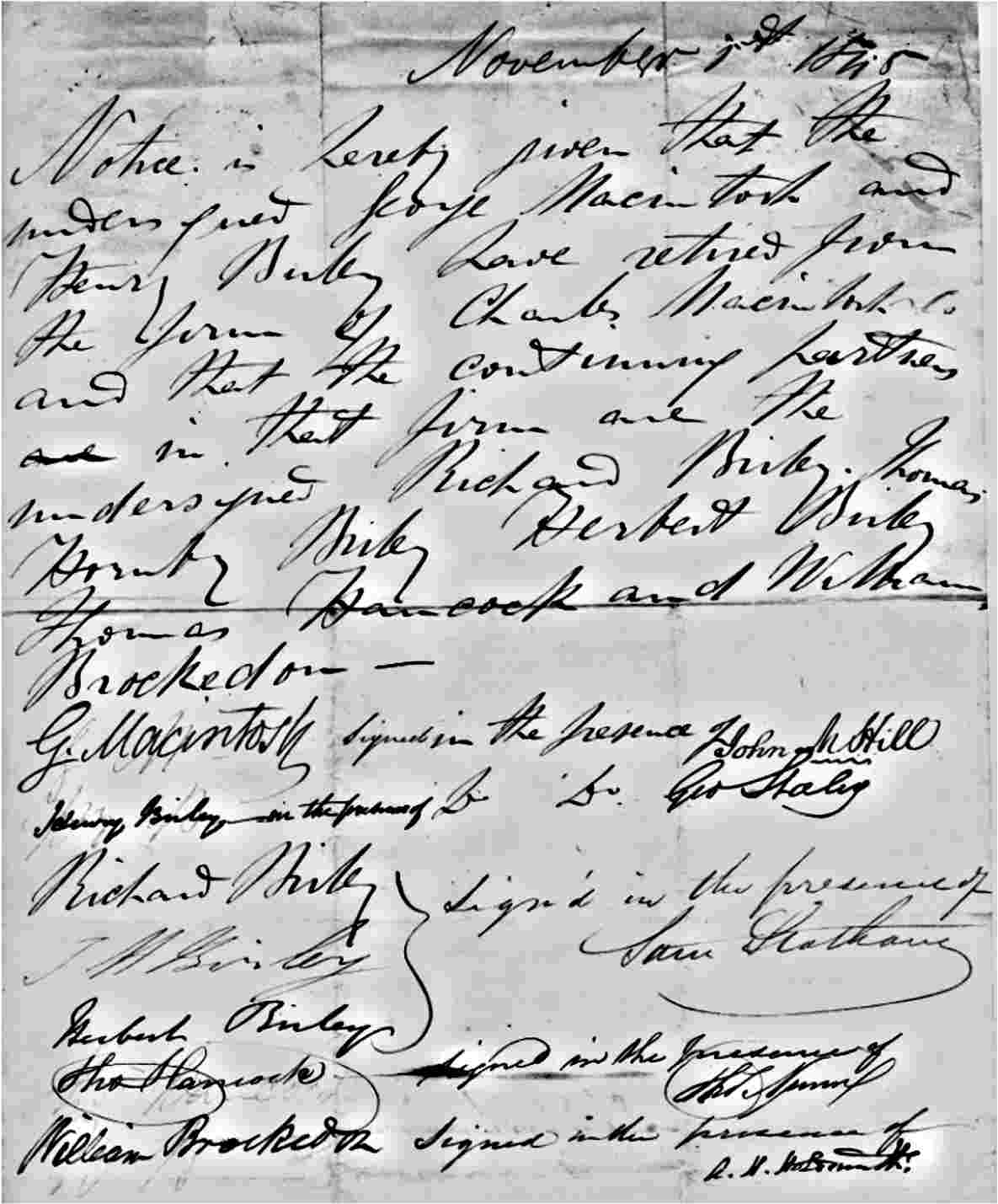

The early 1840’s saw many changes. The company was still in the financial doldrums and in 1842 Thomas’ old business was split from the company and sold to his nephew, James Lyne Hancock, whilst Thomas remained a director of Chas. Macintosh & Co. In 1843, when Charles died, his son George joined the board but after a couple of years he left and there was no Macintosh connection with the company after that. The Notice of Dissolution of Partnership, dated Nov 1, 1845, is a hand-written A5 note which baldly states: Notice is hereby given that the undersigned George Macintosh and Henry Birley have retired from the firm of Charles Macintosh & Co and that the continuing partners in that firm are the undersigned Richard Birley, Thomas Hornby Birley, Herbert Birley, Thomas Hancock and William Brockedon. There follows the signatures of George Macintosh and six of the most famous names in the UK rubber industry of the 19th century:

The discovery of vulcanization, initially by Goodyear in the US and separately by Thomas Hancock in the UK in 1843/4, completely altered the fortunes of the company which was now able to produce a vast range of products made from both vulcanized rubberized fabric and solid rubber. In 1846 the company purchased the ‘cold’ cure’ process of Alexander Parkes for the sum of £5,000. This was the final string to their bow as it enabled thin sheets of rubber, or single texture fabrics, to be vulcanized using sulphur chloride, initially in solution but later in the gas phase. The timing was perfect and the award-winning stand of Chas. Macintosh & Co at the Great Exhibition of 1851 set it on the road to financial security.

Thomas Hancock died in 1865 but Chas. Mackintosh & Co. (with its name unchanged) continued until 1923 when it was taken over by Dunlop. Production on the Manchester site only ceased in 2000 although the original factory was destroyed in 1940. The present factory is now the centre of a regeneration programme for the ‘Southern Gateway’ to Manchester.

Lakelandelements sells a wide range of traditional made-to-measure raincoats to suit every occasion, but on her website Lorraine celebrates the cult of the traditional 'mackintosh' in “Lorraine’s Rainwear Club” which contains a vast number of pages relating to different aspects of this ubiquitous article The site is tricky to navigate but “http://www.lakelandelements.com/rainwearhistory/rainwearhistoryindex.htm” takes you to rainwear history which includes the complete e-text of Hancock’s “Personal Narrative”. Work backwards from here through links in the top right to “chillout room” then “club foyer” and then to “SHOP” in the bottom left. If you love mackintoshes you’ll love this site!

|