If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

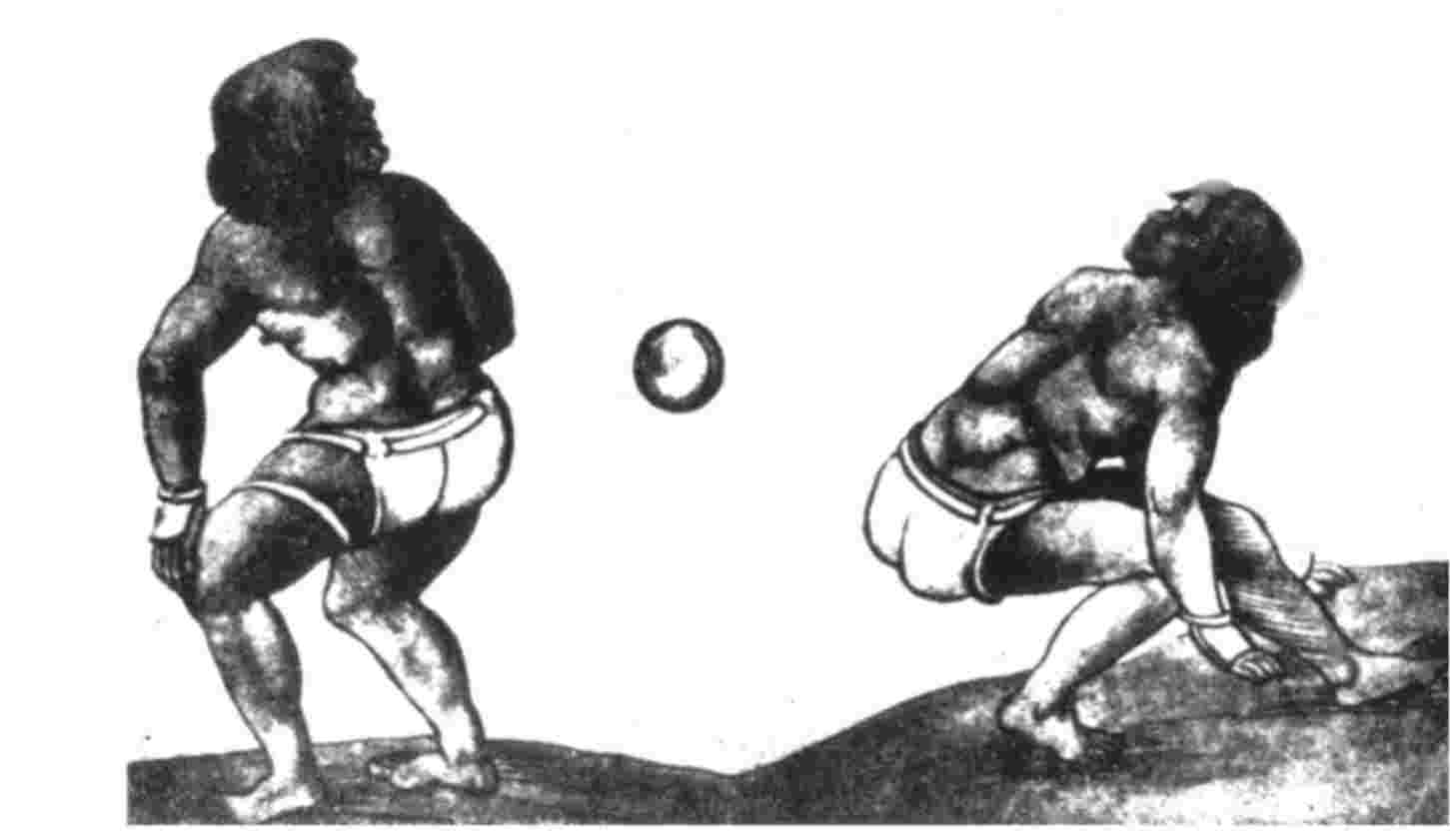

The earliest known ball court is at Paso de la Amada in Mexico and radiocarbon dating has shown it to be about 3600 years old. This places it historically at the interface between the Mokaya and Olmec cultures and only a few hundred years after the early hunter-gatherers had settled into stable residential communities. It is likely that the earliest versions of the game were played on flat courts, as indeed they are in Mexico today, and that the refinement of the sloping sides came with the establishment of permanent settlements. Our knowledge of the older versions of the game is obtained from classic art and archaeology. The ball courts were built in the shape of a capital ‘I’ with the length varying from that of a tennis court to a football field or longer. The central flat strip was narrow when compared with the length and both sides were flanked by sloping banks which were used to keep the ball in play rather like the sloping roofs of a real tennis court. At each end were markers, possibly indicating the ‘goal’ line and a later refinement was the incorporation of eyes or rings, one each side, set in the top of the sloping banks. Most courts were aligned north-south and some locations had a number of different sized ones. The record seems to be held by El Tajin in Veracruz which had eleven whilst one of the most famous Mayan ruined towns known today, Chichen Itza, had at least five. Teams varied in size from two to six and the general idea seemed, initially, to get the solid rubber ball, which varied in size from ten to thirty cm diameter, past the opponents ‘goal line’. The ball had to be kept in the air and all parts of the body could be used except the hands and feet. Each player wore protective clothing, knee and elbow pads, as well as a carved wooden or leather ‘yoke’ round his waist with which, by swivelling his hips, he could hit the ball with considerable force. (Although all experts agree that hands and feet could not be used, two 8th century Mayan sculptures show players holding the ball – half time?)

Points were scored for ‘goals’ and also if the opponents allowed the ball to touch the central flat playing area. With the advent of the rings, additional points were scored if the ball could be passed through the ring. By the time that the Spanish saw the game being played, they were treated to an ‘all fun and games’ version with one writer describing how it was the custom for any player who succeeded in putting the ball through a ring to be awarded the clothes and jewellery of any spectator(s) whom he could catch. Cortez was so amused by the game that he took two teams (and some balls) back to Spain with him where they were painted by the German artist, Weiditz. Although the Spanish were presented with a purely sporting activity, a study of Mayan carvings and pottery shows that the history of the ball game had considerable religious significance and was also bound up with ritual sacrifice. For instance, a relief in Izapa shows a decapitated (defeated) ball game player at the feet of the victor who holds his decapitated head whilst a relief at El Tajin shows the classic Mayan scene of the loser having his heart cut out as an offering to the underworld to release the Sun for another cycle. There are many references to defeated warriors being forced to play against their captors prior to execution. We do not know if they were freed if they won but in one illustration the losers were rolled up into balls and then rolled down an adjacent pyramid to their death. The use of the decapitated head, encased in rubber, as a ball is described in the Popol Vuh. The religious significance of the ball game is most completely described in the Popol Vuh and the actual game, as played in the ball court is a re-enactment of Mayan mythology with the movement of the ball representing the cyclic journeys of the Sun and Moon through the sky, sinking to earth only to rise again. Whilst most ball courts are in prominent positions nears the cultural/religious centres of towns, some have been found on at the boundaries of adjacent kingdoms and it is believed that these were used for battles between rulers’ champions to settle inter-kingdom rivalries and disputes. |

|