If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

Natural rubber, Indiarubber or Caoutchouc are all names for the solid elastic material isolated, one way or another, from the ‘milk’ or latex of various plants. Whilst these plants tend to occur in the tropics, there are many which grow in the temperate zones and also produce this material although not in any commercial sense. Perhaps the most common source in the UK is the dandelion – snap its stalk and the white fluid is latex which will dry to give rubber. The latex is therefore the white milk-like fluid which is obtained by wounding the plant and in the case of the most common commercial source today, the tree Hevea braziliensis, by cutting a sloping incision in the outer bark from which the latex will ‘bleed’ and then refreshing the wound by removing slivers from the surface of the cut on subsequent tapping days. the word ‘rubber’ itself did not come into use until the 1770’s (see J Priestly in the time line) and it was another hundred or more years before it was adopted by scientists who preferred the ‘classical’ caoutchouc. In the 20th Century the application of the one word expanded in common usage to include an ever-growing range of synthetic elastomers. It is interesting to look at the origins of the word caoutchouc a little closer but first let us consider the name of the trees from which this material comes as this also provides an interesting story! The ‘Rubber’ Tree

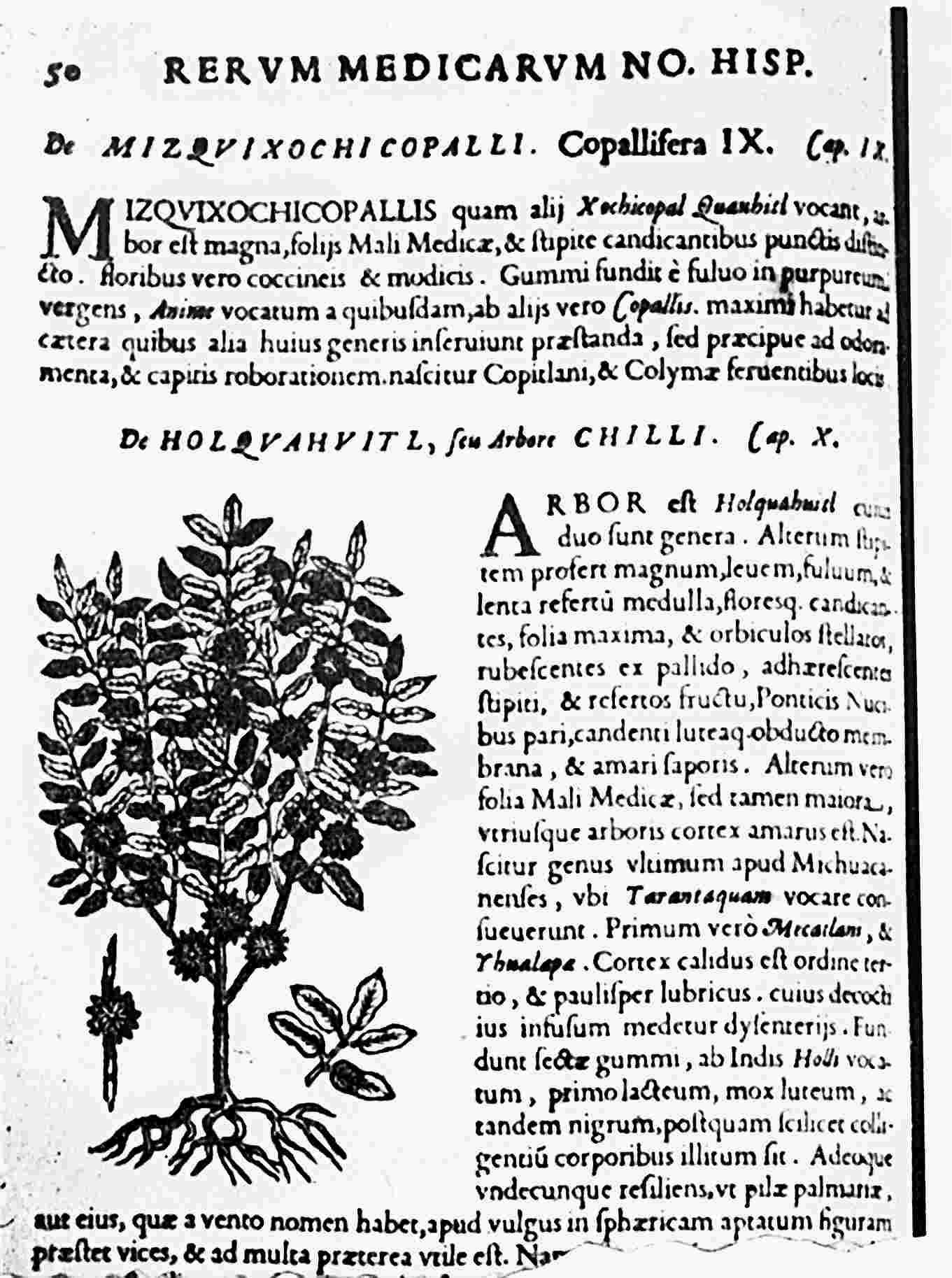

In 1723, Father AJ de la Neuville wrote of the peculiar gum (rubber) which the Indians of French Guiana used to make various artefacts and ornaments. From his description it seems likely that this gum was obtained from a vine of the order of Apocynaceate – probably landolphia. The Castilla elastica was also the tree described by la Condamine and from this came the rubber samples which he sent to France in the 1730’s but a decade later he saw the ‘syringe tree’ and did not realise it was different. Almost certainly he had not seen the original Castilla but had only heard reports of it. It was this ‘syringe tree’ tree which François Fresneau found in French Guiana and wrote about to la Condamine and the Paris Academy of Science. By a pure fluke he appears to have found the one and only Hevea braziliensis in that country and it is not surprising that his drawings caused confusion some time later! He did not give it its current name but just referred to the ‘enema tree’ after the stories of the uses to which the syringes prepared from the ‘syringe tree’ were put. In 1775 JCF Aublet published a book on the plants of French Guiana and in it he recorded a ‘rubber tree’ which we now know could not have been the same as Fresneau’s but at that time, Aublet believed that his tree, la Condamine’s and Fresneau’s were the same. He came up with the name Hevea peruviana, thus giving la Condamine credit for his early discoveries. With a second thought he then reasoned that, since he had not seen la Condamine’s tree but only the ones in French Guiana, he had better play safe so he re-named his tree Hevea Guyanensis (its present name). This upset many people who objected to a ‘localised’ name being given to a tree found all over the north of South America. At the same time, Aublet was castigating Fresneau for the poor quality of his sketches which looked nothing like his (Aublet’s) tree. It was left to the Dutchman, Arnoud Juliaans to study all the literature and state the obvious – THERE WERE AT LEAST TWO DIFFERENT TREES. (see 1780 below). In 1807 Persoon called the ‘syringe’ or ‘enema’ tree Siphonia elastica whilst in 1811 Willdenhow, Director of the Berlin Botanical Gardens came up with the name Hevea braziliensis. The dispute was only resolved in 1865/6 by Müller who suppressed Siphonia in favour of Willdenhow’s name which illustrated the Aztec origins of rubber technology and the geographical location of the tree. It is now appreciated that Hevea braziliensis is almost completely located south of the river Amazon in north-west Brazil, north Bolivia and east Peru whilst other ‘rubber’ trees of the genus Hevea are located north of the river to a latitude of about 6°N. Finally, the seeds which Henry Wickham collected in 1876 were from the Tapajos region of Amazonia, south of Santarem, and were Hevea braziliensis, as were the seedlings of Robert Cross. By coincidence Kew had acquired what proved to be the highest yielding plants which gave the best quality rubber and, historically, had the most appropriate name! The Names For Rubber There are four new-world native words for rubber and these are written as Cauchuc (or caoutchouc), Hevea, Olli and Kik. It has been said that there is a relationship between caoutchouc and devil worship and sacrifice but before considering this, let us deal with the three other words. Kik is a word from the Mayan language of the Yucatan peninsula and means ‘blood’ but it has never been used in the west to refer to rubber. Olli comes from the Nahuatl language of ancient Mexico and, because of the locations of the various rubber-bearing trees, always refers to the Castilloa elastica. This is obviously the root of the current Mexican word for rubber – Ule. Hevea was la Condamine’s word taken from the Equadorian Indians for the rubber-bearing tree itself and has never been used in modern times to mean rubber. The modern word for rubber in Peru and Equador is jebe. This brings us to Cauchuc/caoutchouc which is important in that it is the basis for the current French, German, Spanish, Italian and Russian words for the material – and is complicated as it seems to have origins in at least four different languages. The Maïnas Indians of Peru have the word meaning ‘juice of a tree’ whilst other authorities have identified the word with the Tupi Indians of the Brazilian Amazon and also the word Caucciú from the Caribbean. Each could, of course, be relevant depending on which explorer met which native! The interpretation publicised by Vicki Baums’s eponymous novel “Weeping Wood” is that of WH Johnson who claims that caoutchouc is a corruption of caaocho, itself derived from Caa, meaning ‘wood’ and o-cho meaning ‘to run’ or ‘weep’. Perhaps the final word should lie with The Kechuan language of the Peruvian Incas as this was the most developed of four Indian languages. Here the 1608 dictionary of Diego Gonzalez Holguin translates cauchu as ‘he who casts an evil eye’ whilst in 1653 Bernabé Cobo noted that the Mexican olli and the Peruvian cauchuc refer to the same material obtained from Castilloa elastica. It should be remembered that applications of rubber to witchcraft, sorcery and ritual sacrifice (as well as the ball game) predate its more utilitarian uses. Other rubber-producing trees of historical interest are listed below. For various reasons none challenged the Hevea braziliensis which today produces virtually all the natural rubber used worldwide.

Also of related note are:

|