|

If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

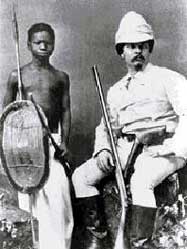

Henry Morton Stanley is known to the world as the American journalist who, in November 1871, issued the immortal greeting:’ Dr Livingstone I presume’ when he located the missing explorer at Ujiji. In fact he was neither ‘Henry’, ‘Morton’, ‘Stanley’ nor American and it is arguable whether his journalism was based more on fact or on fiction. He was born in Wales in 1841, one of several illegitimate children of Betsy Parry, and christened ‘John Rowlands - Bastard’, the first of many indignities which contributed to the character which King Leopold II was to find so useful. The first six years of his life were spent with his grandfather who did not believe in sparing the rod and, when he died, John was deposited in the St Asaph Union Workhouse. Here he seems to have been the recipient of the worst kinds of Victorian sexual and physical abuse but gained a passion for geography, an elegant script and a bible as a prize from a local bishop. At fifteen he left St Asaph’s and for two years lived as the ‘poorhouse boy’ with various relatives before shipping to New Orleans. In a series of moves which would be recognised by any psychiatrist today he then began a process of re-invention, taking on the name of the merchant who befriended him when he landed and inventing a whole new autobiography. There is no doubt that his early childhood left him with what would today be called sexual hang-ups and it can be no coincidence that, in years to come, he departed on two of his African journeys soon after becoming engaged. Neither lady waited for him. After a stint in the American Civil War – fighting for the Confederates at the battle of Shiloh and then for the Union navy, bombarding Confederate ports in North Carolina - he started his journalistic career writing freelance articles. He then covered the Indian wars for a variety of eastern papers. The conflict between the papers’ desire for stories of blood and thunder and the fact that the wars were virtually over and that Stanley’s time was spent covering peace missions was easily resolved as his fictional reports of the Indians on the warpath showed. His reports and style were appreciated by the publisher of the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett Jnr., who hired him to cover the British-Abyssinian war. Here, foresight and luck played equal parts in his advancement. He had already bribed the telegraph operator in Suez to send his dispatches before all others and, just after his report of a British victory, the telegraph cable out of Suez broke so no more dispatches could be sent. This scoop, in June of 1868, resulted in his being given a permanent position as a roving reporter on the Herald but it took until the end of 1871 for him to become a household name, as famous as the explorer whom he had found. This mattered to Stanley who never regarded exploration as anything more than the establishment of a factual framework within which he might weave his arguably fictional tales of daring-do and thus obtain the riches he never had as a child. His books were so popular that it would be fair to identify him as the first of a long sequence of professional travel writers but, once again, he was fortunate, Livingstone died in Africa and did not return to Britain where his story might well have conflicted with that of Stanley’s as told in ‘How I found Livingstone’. Stanley was now thirty years old. Yet again his past returned to haunt him as the ‘upper crust’ Royal Geographic Society refused to acknowledge his exploring abilities and rumours about his birth began to spread. This could be professionally damaging to an ‘American’ writing for an anti-British paper in the US. His insecurity was further increased when he discovered that his fiancée had married whilst he was away. His answer - to return to Africa - could be considered escapism or a need for more background for his next book. Finance was available from Gordon Bennett, Levy-Lawson of the UK Daily Telegraph and others for an Anglo-American expedition to solve a number of geographical problems relating to the land west of Lake Tanganyika and, particularly, to establish the relationship between the rivers Lualaba, Nile, Niger and Congo. Livingstone had thought that the Lualaba formed the headwaters of the Nile but Lovatt Cameron believed it fed the Congo. Stanley initially favoured the Niger but slowly came to prefer the Congo. The world wanted to know and he could see money in a book. The expedition set off in 1874 with Stanley, three other whites whose lack of experience suggested that they had been chosen so that they would not detract from Stanley’s glory, and their main means of transport, the Lady Alice, a forty foot steam launch which divided into five sections for portage. The boat was named after Stanley’s second fiancée, the seventeen-year-old Alice Pike. The expedition also contained over 300 Africans. Stanley’s was perfectly happy to fight his way past any tribal opposition, particularly when it consisted of bows, arrows and spears with the occasional antique muzzle-loader. He noted that ‘we have attacked and destroyed twenty-eight large towns and three or four score villages’. However, when necessary, he was capable of a more subtle approach, illustrated in his conversion of the Emperor of Uganda to Christianity. This was brought about by making him aware of the church’s eleven commandments, the one we would not recognise being that man must ‘honour and respect kings as they are envoys of God’. Starting down the Lualaba, Stanley travelled several hundred miles before the first portage round ‘Stanley Falls’ and then he had a clear run of almost 1,000 miles to ‘Stanley Pool’. Lest it be thought that his egotism was running a little high, he named Mount Gordon Bennett, the Gordon Bennett River, the Levy Hills and Mount Lawson after his main sponsors. The naming of ‘Stanley Pool’ was at the insistence of one of the other whites, Frank Pocock, or so Stanley claimed but as Mr Pocock, like Stanley’s other two white companions, died on the expedition we can only take his word for that. The final 200 or so miles west of Stanley Pool to the coast were a continuous string of rapids and waterfalls which made Stanley realise that he was on the River Congo. The boats were abandoned and a desperate four-and-a-half months of marching through the jungle was needed to arrive at Bomba. The epic ’Through The Dark Continent’, published by Stanley in 1878, tells all from his point of view in his established and popular style, although one fact which is missing is the number of native survivors. We know that Stanley, alone of the four whites who set out, survived and that the death toll amongst the natives was massively high. Perhaps Stanley’s failure to record this detail just reflected his lack of interest in the trivia of his successful expedition. The only sour note was to be sounded when he discovered that his second fiancée had preferred the ‘bird in the hand’ and had married an American railway heir a few months after they had separated. He would have been more distressed to know that in later years, after his death, she claimed remorse that she had not waited for him and professed that it was her spirit, together with the physical presence of the Lady Alice, which had motivated and carried him across Africa. Leopold had been watching Stanley. Earlier, Lovatt Cameron had annexed the Congo in the name of Queen Victoria – only to have the British Government reject the annexation as soon as it heard of it! Leopold’s immediate problem now was how to recruit Stanley without alerting the British. He therefore resolved to employ Stanley to explore the Congo basin for his ‘front’ body, the AIA. A little early discussion with Stanley seemed a good idea so he sent two emissaries to meet him at Marseilles, where his train had stopped en route to Britain from Italy. Stanley was not interested; he wanted plaudits from his countrymen (the British) and time to write his book. By June 1878 Stanley had become tired of the negative attitude of the British Government, which was too tied up in Egypt and the Nile to consider further African undertakings, so he travelled to Brussels for a meeting with Leopold. The two got on well but Stanley emphasised that the first stage of any useful opening-up of the Congo required a railway round the lower falls and rapids. Funding was a problem but a proposal from the Dutch traders at the mouth of the Congo for a ‘Study Syndicate’ fitted nicely into the ostensible ‘charitable’ purposes of the AIA and a group of European financiers agreed to support this. The syndicate came into being as the ‘Comité d’Etudes du Haut-Congo’. Leopold wrote to Stanley: ’It is a question of creating a new State as big as possible and running it … there is no question of granting political power to Negroes … the white man will head the stations which will be populated by free and freed Negroes. Every station would regard itself as a little republic The work will be directed by the King (Leopold) who attaches particular importance to the setting up of the stations … the best course of action would be to secure concessions of land from the natives for the purposes of roads and cultivation and to found as many stations as possible …should we not try to extend the influence of the stations over the neighbouring chiefs and form a Republican Confederation of native freedmen. The President (of the Confederation) will hold his powers from the King.’ The emphasis on ‘freed men’ fitted in with the aims of the AIA and gave Leopold the time he needed to implement his real schemes, more honestly set out in a private letter to Stanley in August 1878. Stanley was to acquire as much land as possible by purchase or concession on behalf of the Comité which would set out the laws of this ‘Free State’ with Leopold, as a private citizen, at its head. Although Stanley obtained close to 1,000,000 square miles of the Congo for Leopold, the latter was not happy as the French, through Count Savorgnan de Brazza, established a camp at Stanley Pool, the site of the future Brazzaville. What Stanley did not know was that the Comité d’Etudes du Haut-Congo no longer existed! In November 1878 Leopold announced to his shareholders that most of the money used to found it had been spent and the rest was committed to contracts already underway. The Comité d’Etudes du Haut-Congo was immediately replaced by the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC) with 100% funding from Leopold. With his land and position reasonably secure he could nopw concentrate on transport and infrastructure. In 1890 Stanley’s railway was started at Matadi. Three years later it had advanced 14 miles at a cost in African life which is, even now, unknown. The official figures claimed 1800 non-whites and 132 whites but less official (and more reliable?) sources suggest that the 1800 figure only relates to the first two years of its construction. Nevertheless, the line was extended to Stanley Pool over the next five years and was then open for business. Three weeks of portage were reduced to two days of steam-powered transportation. By now people were beginning to take note of Leopold’s ambitions and activities. One of the earliest attempts to bring him to some accountability was initiated by a black American soldier, lawyer and preacher, James Washington Williams. Williams was already known in America as a proponent of black civil rights and in1889 he wrote to Leopold suggesting that he could recruit black Americans to work in the Congo where they could advance themselves in a way impossible in the US. He came to Europe, met and was initially impressed by Leopold but in 1890 he set out for Africa where he spent six months touring the Congo. He was a civil rights activist and what he saw sickened him. His response was to write an ‘Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II’ which was also published as a pamphlet and widely distributed throughout Europe. He wrote a similar letter to the President of the United States of America, President Harrison. In the ‘Open Letter’ he accused Leopold on eight major points. Those relevant to Stanley were: “Stanley used a range of crude conjuring tricks to persuade the natives that he had supernatural powers and to induce them to sign over their tribal lands for trivial recompense.” “Stanley was not a hero but a cruel foul-mouthed tyrant.” However, in 1890 Stanley was safe in England. His story about his struggle to find Emir Pasha was published in 1890, the year that Joseph Conrad went to the Congo and later recaptured his experiences in 'Heart of Darkness'. In the following year Stanley visited the United States and Australia on lecturing tours. He was knighted in 1899 and in 1895-1900 he sat in Parliament. He died in London on May 10, 1904 and is buried at Pirbright, Surry.

|