|

If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

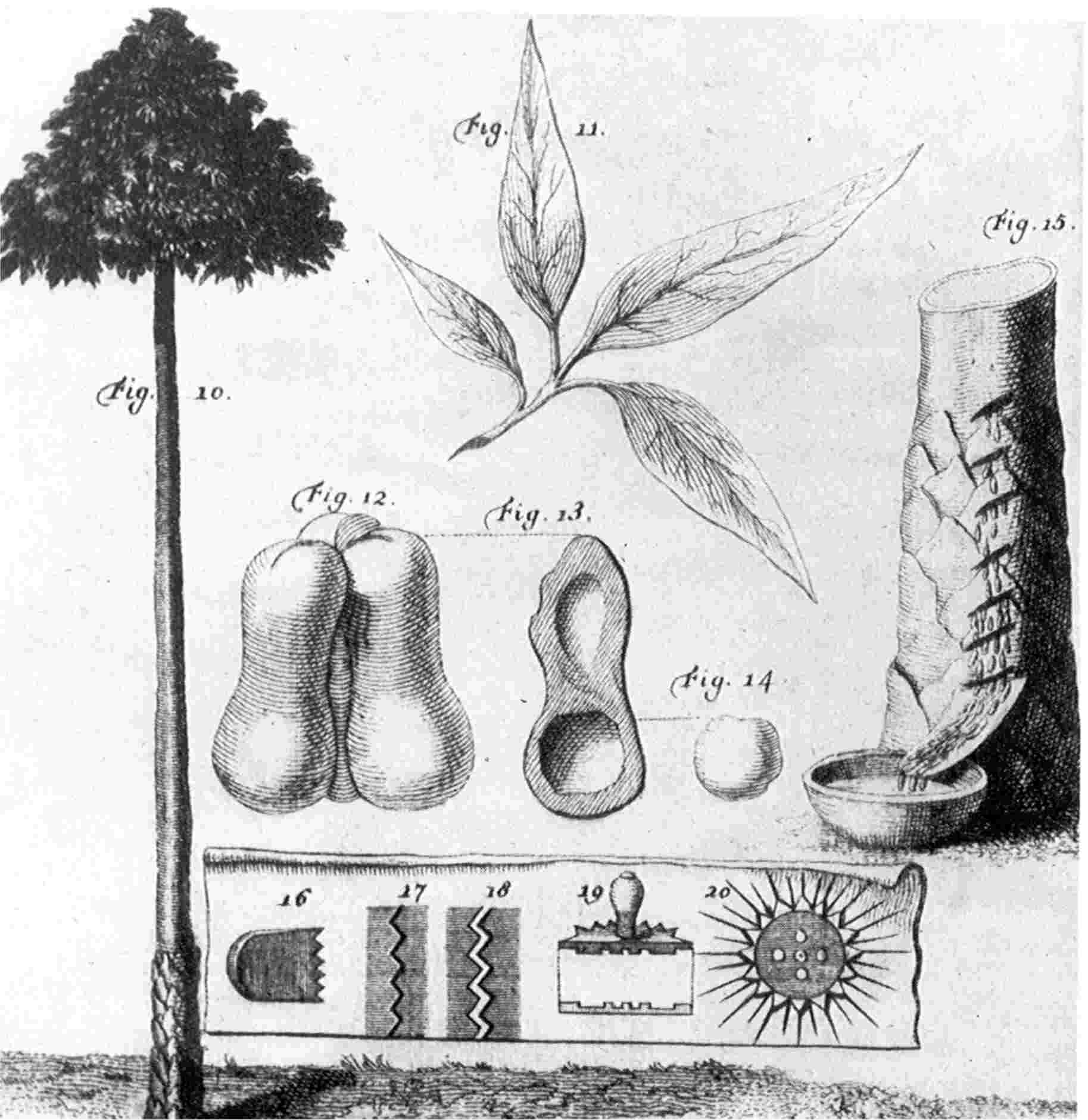

Charles Marie de la Condamine studied mathematics at the Jesuit College of Louis-le-Grand in Paris. On leaving the College he joined the French army when war broke out. Although he was recognised for his bravery, he soon decided that army life did not suit him. In 1730 la Condamine joined the Académie Royale des Sciences and sailed to Algiers, Alexandria, Palestine, Cyprus and Constantinople where he spent five months. On his return to Paris he published mathematical and physical observations of his voyage. In 1735 he joined an expedition Peru to measure the length of a degree of meridian at the equator. The expedition was led by Louis Godin and the third scientist was Bouguer. The three arrived by different routes, La Condamine going overland from Manta, the other two sailing to Quito where they joined up. Soon after his arrival in Quito, in 1736, la Condamine sent a package of rubber to the Académie with a long memoir describing many aspects of its origins and production. These included the words "Hévé" as the name of the tree from which the milk or "latex" flowed and the name given to the material by the Maninas Indians :"cahuchu" or "caoutchouc". He later described the smoking procedure by which the natives made the rubber stable and the wide range of goods which were produced, including the following: "They (the natives on the banks of the Amazon) make bottles of it in the shape of a pear, to the neck of which they attach a fluted piece of wood. By pressing them, the liquid they contain is made to flow out through the flutes and, by this means, they become real syringes." From this the Portuguese called the tree "pao de Xiringa" (syringe wood) and the rubber tappers or harvesters "Seringueiros". The tree which la Condamine called “Hévé” was "Castilloa elastica", but he did not realise that the one he described a decade later, the "pao de Xiringa" or Seringa tree, was different, "Latex", the word used by la Condamine to describe the juice of the tree, was derived from the Spanish word for milk and remains in use to this day. the perceived source of the material, soon became shortened. Godin, Bouguer and la Condamine were soon involved in arguments which resulted in them all making (different) independent measurements. The work was completed in 1743 and the three began their returns by different routes. La Condamine’s began with a four month journey down the Amazon river. His was the first scientific account of the Amazon which he published as Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi a l'équateur (1751). Before returning to France, la Condamine met Fresneau who was a trained engineer and amateur botanist. Fresneau became infected with la Condamine's enthusiasm for rubber and was the first western person to consider it as a potential industrial material. By February 1745 La Condamine was back in Paris after his ten year journey. He returned with many notes, 200 natural history specimens and works of art. Fresneau remained in Guiana, detailing all aspects of rubber production, treatment and usage and forwarding his reports to his friend for publication. In 1751 la Condamine presented a paper by Fresneau to the Académie (eventually published in 1755) which described many of the latter’s findings and this can truly be called the first scientific paper on rubber.

La Condamine was a close friend of Maupertuis for many years. He spent much effort in the last part of his life campaigning for inoculation against smallpox. His passion on this topic was partly due to the fact that he had suffered from smallpox as a child. |