|

If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

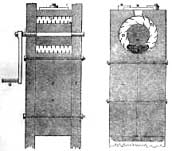

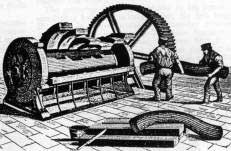

This page briefly describes the life of Thomas Hancock; however he was only one of a remarkable and inventive group of brothers who contributed uniquely to the development of Britain through the industrial revolution. John was also in the rubber business, Walter designed and built the first steam vehicles to carry passengers on the common roads of Britain whilst Charles arguably began the information superhighway when he developed a way of coating undersea telegraph cables with gutta percha to make them waterproof. Read the detailed history of the family from 1653 to the present day in by John Loadman & Francis James. OUP, 2009, ISBN978-0-19-957355-4. Thomas Hancock was born in 1786 in Wiltshire and of his childhood we know little. His father was a cabinet maker and it is probable that he learnt the skills of that trade because in 1815 he appears in London, in partnership with his brother, as a coach builder. His interest in rubber seems to have spring from a desire to make waterproof fabrics to protect the passengers on his coaches and by 1819 he recalled beginning to experiment with the making of solutions of rubber. At the same time he was making elastic thread by the simple but tortuous process of slicing rubber bottles into thin sheets and then slicing the sheets into strips. This, not surprisingly, generated a great deal of waste so in 1820 he invented a machine to shred the waste. What his machine gave him was a warm homogeneous mass of rubber which could then be shaped, mixed with other materials and much more easily dissolved than the virgin rubber then available. Rubber Technology had arrived in the shape of the highly secret ‘Pickling machine’ or masticator as we know it today. This machine as illustrated was operated by one man and could hold only 3 ounces of rubber. As soon as he realised what his prototype 'pickle' could do he had made a cast iron version and by 1821 he had progressed to a two-man machine, holding a pound of rubber, then a horse-powered machine (15 pounds). By 1840 his machine was as illustrated below (right) and could handle charges up to 200 pounds. His ‘shearing pins’ had now given way to corrugated rollers. It should be noted that he never patented his ‘Pickle’ preferring to rely on secrecy – an important point which will be returned to later.

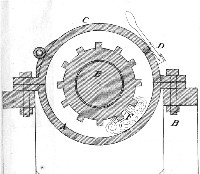

As soon as Hancock made his ‘pickled’ rubber he began experimenting further with rubber solutions and in 1825 he patented a process for making artificial leather using rubber solution and a variety of fibres. His choice of solvent, rubber in coal oil and in turpentine was probably influenced by Macintosh’s patent of 1823. In the same year he began collaborating with Charles Macintosh in the manufacture of his ‘double textured’ material although at this stage Macintosh did not trust Hancock sufficiently to use his rubber solutions. By 1830 it was obvious to all that Hancock’s solution, prepared with his masticated rubber, was much better than that of Macintosh and so the full cooperation began, one feature of which was the construction of an automated spreading machine to replace Macintosh’s paint brushes. In 1834 Hancock’s London factory burnt down and Macintosh had already closed the Glasgow factory so all work moved to Manchester where, in 1838, another fire destroyed that factory. A new one was quickly built and business continued as before although Macintosh’s 1823 patent had expired in 1837. It was only in 1837 that Hancock finally patented both his masticator and spreader in the same UK patent (7344). The masticator included in this patent appears to be his earliest iron version and the functional part is shown in the cross section below as it appears in the patent. The reasons for his reluctance to patent earlier are addressed in ‘Hancock and Macintosh at Law’ later in this article.

The truth about Hancock and his ‘discovery’ of vulcanization is unlikely ever to become clear. It is an established fact that Stephen Moulton brought samples of Goodyear’s vulcanized rubber to the UK and that in 1842 some fell into Hancock’s hands via Mr Brockedon but there the clarity ends. Brockedon says in an affidavit that he never heard or knew of Hancock analysing the Goodyear samples and Hancock verifies that in his ‘Personal Narrative’ claiming that he had been experimenting with sulphur for many years himself. A number of chemists swore that, even if he had analysed Goodyear’s material, this would not have given him enough information to manufacture them. Moulton, however, claims that some of Hancock’s employees did carry out the analyses and one Mr Cooper had sworn that he did. Alexander Parkes, the inventor of the ‘cold cure’ process, went one step further and claimed that both Hancock and Brockedon had admitted to him that their experiments on the Goodyear vulcanizates had enabled them to understand what he had done. Whatever the truth, it is a fact that Hancock patented his process of vulcanization on 21st November 1843, eight weeks before Goodyear (30th January 1844). Hancock’s business flourished and it is hard to find an article today which is made of vulcanized rubber which does not feature in his ‘Narrative’. He also described hard rubber (vulcanite or ebonite) and soon after, blown sponge, although the latter never achieved significance during Hancock’s lifetime. One more patent is worthy of note. In March 1846 Alexander Parkes patented the vulcanizing of single texture fabrics in a ‘cold’ process using sulphur chloride in carbon disulphide solution. The patent was bought by Hancock (Chas. Macintosh & Co.) almost immediately for £5000 and added the final string to the company’s vulcanising empire. The firm had large display stands at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London and at the International Exhibition of 1855 in Paris. In 1857 Hancock published the story of his life’s work as ‘The Origin and Progress of the Caoutchouc or India-Rubber Industry in England’. He continued to work until his death in 1865. To read the history of Chas. Macintosh & Co., check here. To read the full text of Hancock's "Personal Narrative" click here (This will take you away from bouncing-balls website) (to read Thomas Hancock's obituary in 'The Mechanics' Magazine of April 7th 1865, please click here)

In Hancock’s ‘Personal Narrative’ there is little to indicate the major legal battles which he fought to preserve his position in the UK. Indeed, there is no direct mention of Charles Goodyear or Stephen Moulton and the argument which ensued for many years over who actually discovered vulcanization.

The earliest of the major UK cases took place in 1836 with Chas Macintosh & Co. as plaintiffs and Wynne Ellis as defendant. The plaintiff’s case was that Everington and Ellis had infringed Charles Macintosh’s patent of 1823 for the manufacture of ‘double textured’ cloth. In 1824 Macintosh had approached Wynne Ellis, perhaps the riches silk merchant in the UK, for financial backing for his new material. Some of Wynne Ellis’ silks were treated at Macintosh’s factory at Glasgow but he was not sufficiently impressed to help finance Macintosh’s expansion plans. However, in 1835, Everington and Ellis began to market ‘Fanshawe’s Improved India Rubber Cloth’ which appeared in all respects identical to that manufactured by Hancock and Macintosh. The latter were just starting to make money and were not prepared to share it with interlopers! The situation was further complicated in that whilst they were preparing the court case, they applied for an extension of the 1823 patent. The application was heard in December 1835 and it was ruled that a decision on that should be held over until 1837 – after the pending court case. The case for Wynne Ellis was threefold in that evidence was produced that ‘double textured’ garments had been produced in Demerara since the end of the 18th century using latex as the adhesive, that Charles Green had used rubber solution and the double texture procedure to manufacture balloons and that it was obvious by inspection of the current output from the Macintosh factory that it bore little resemblance to that produced in 1823 and therefore the process must be different and the patent could not apply. The first point was quickly dealt with (surprisingly) when it was agreed that what happened using latex was not the same as when using a rubber solution. It was surprising because the plaintiffs had emphasised that the solution was not important but that the patent referred uniquely to the ‘double texture’ in combination with a solution. The second witness was quickly disposed of when it was shown that his ‘double texture’ was an overlapping of seams and the solution was just a mastic. This left the final point, which put Hancock and Macintosh in a difficult position since the whole manufacturing operation had been the subject of on-going development and it had been carried out in secrecy without the benefit of patent protection. Their first witness was an operative who had left the business in 1825 when Macintosh moved from Glasgow to Manchester and he knew only the original procedure so could give away no secrets but they then had to produce the man who was currently in charge of the manufacturing operations and who knew the development of the spreading machinery. By Hancock’s design however, he knew nothing of the composition of the solution and particularly of the masticator. They got away with it and were victorious but opposition to an extension of the patent was so great that they decided to withdraw it and, at last, opted for the only protection left – to patent both the masticator and the spreading machinery. Reading the patent today and knowing of the use of the masticator, Macintosh’s preference for purified coal tar and naptha but Hancock’s preference for thick viscous solutions prepared with naptha and turpentine mixed solvent etc. one must doubt whether the same verdict would have been reached today! Macintosh was lucky to allow for the spreader by saying in the patent “…with a brush or other suitable instrument lay upon the surface of each (fabric) a uniform layer…” but when it comes to the adhesive: “…cemented together by means of a flexible cement…prepare the caoutchouc by cutting into thin shreds or parings and then steep it in the substance used in making coal gas, commonly called coal oil…10-12 oz to 1 gallon of oil …to give a thin pulpy mass… pass through a fine wire or silk sieve… resembles thin transparent honey…” it all seems very specific and would not seem to allow for masticated rubber or turpentine! In 1847 the first major shipment of vulcanized rubber products, mainly rubber over-shoes, arrived in the UK from the States. This had the potential to undermine the position of Chas. Macintosh & Co. and had to be contested on the strength of Hancock’s prior patent. This was found to be valid and then Macintosh & Co. granted The Hayward Rubber Company of Connecticut sole rights to import and sell vulcanized rubber footwear in the UK (for a consideration). In 1849, Chas. Macintosh & Co. began to prepare a case against a UK importer who was by-passing Hayward and yet again, Hancock’s patent was found to stand. With these decisions in his favour Hancock felt able to challenge the biggest thorn in his side – Stephen Moulton – who was manufacturing vulcanized rubber goods from his factory in Bradford-on-Avon. Hancock vs Moulton Moulton had taken out a patent for the vulcanization of rubber in 1847 in which he used ‘lead hydrosulphite and artificial sulphured of lead’ which, he claimed did not infringe Hancock’s patent which just used sulphur, or Goodyear’s which used lead oxide and sulphur. He also mixed ‘in the dry’ whereas Hancock’s patent was solely concerned with applications of solutions of rubber and there were other differences of varying importance which had allowed the patent to be granted. He further raised the interesting point that Hancock’s patent was, in any event, invalid because its deposit paper of 1843 was not followed through in the final specification. The title was: ‘…For improvements in the preparation or manufacture of caoutchouc in combination with other substances, which preparation or manufacture is suitable for rendering leather cloth and other fabrics waterproof, and to various other purposes for which caoutchouc is employed’. Whilst the text begins with: ‘…Preparation or manufacture of caoutchouc in combination with other substances, consists in diminishing or obviating their clammy adhesiveness and also in diminishing or entirely preventing their tendency to stiffen and harden by cold and become soften or decomposed by heat, grease and oil’. The eventual decision of the Vice-Chancellor’s court was a remarkable piece of fence-sitting. The judge found for Hancock on all counts but pointed out that because he had taken so long to bring Moulton to court (1847-1852) he felt unable to make an injunction against Moulton but ordered the motion to ‘stand over’ so that the plaintiffs could take further action if they so wished. The American shoe trade was not at all happy with this situation and a Mr Ross, who was importing American shoes into the UK but not via Hayward, challenged Macintosh & Co to sue – which Hancock duly did. After all the old ground was gone over again the jury failed to reach a verdict but the fighting spirit of the anti-Hancock group was high and they issued a writ of scire facias against Hancock, essentially putting the onus on him to provide evidence that he had actually carried out all the work described in his patent. Rex vs Hancock This trial came to court in mid 1855 and even Goodyear attended to stake his claim to royalties from Hancock should the latter loose. In the end it came down to one question. When Hancock had taken out his patent in 1843 had he understood and achieved vulcanization? If he had only done this between 1843 and the final specification in 1844 then his patent would fall. In January 1856 the saga came to an end with the jury finding for Hancock and Moulton having to pay an annual licence to use his own process! Addendum But that is not quite the end of the story because some bright spark realised that there were two patents by Goodyear and Hancock covering the UK. In England Hancock’s preceded that of Goodyear by some two months but in Scotland the position was reversed with Goodyear’s application dated three months ahead of that of Hancock and the final specification being just one month ahead. In 1856 the North British Rubber Company was founded in Edinburgh being shipped over, lock, stock, barrel and key workers from the US. Legal opinion was that Hancock’s delay in filing his Scottish patent would probably lead to defeat if he went to court and since it had so little time left to run the battles at last ceased. Hancock’s very abridged reports of his trials in his ‘Narrative’ paint him very much as the poor injured party just trying to protect his interests whilst the rest of the rubber world is bent on destroying him (and the monopoly he aimed to obtain in the UK). As with most of life the truth probably lies in the middle somewhere. What is certain is that without Hancock’s drive and inventions between 1820 and 1850 the UK rubber industry would never have achieved the advancements it did and the UK would be a worse place for that! |