If you have come to this page from a search engine please click here for a full site map and access to all site pages

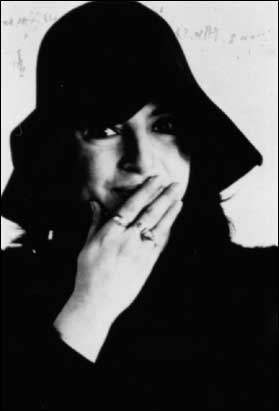

Eva Hesse occupies an unusual position in being a world-renowned artist who, towards the end of a short career, specialised in the use of natural rubber latex and fibreglass to create artworks and yet seems unknown to the world of the plastics & rubber historians.

In 1967 she discovered latex and, as she investigated it, she became fully aware that it was a transient material which would eventually degrade irreparably. She also found fibreglass and polyester resin and was fascinated by the irregular shapes and surfaces she could create with them. This led to her creating elaborate, obsessive pieces of sculpture involving multiple repetitions. It was the concept, rather than the actual finished artwork which interested her and for many of her later pieces she left the fabrication to others. By now she was exhibiting, both solo and in groups, in a wide range of exhibitions and was about to be ‘seriously discovered’. Victor and Sally Ganz had begun their legendary collection with the purchase of Picasso's “Le Rève” for $7,000 in 1941. They were making one pf their regular shopping tour of galleries when, in November 1968, Victor viewed Eva's first exhibition at the Fischbach Gallery and was fascinated by her strange constructions of sheet metal, staples and rubber tubing. He made his first purchases of her works. By this time they had already amassed one of the world’s finest private collections of modern art and Eva’s artworks were on display in the Ganz’s house, given equal ranking with works by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Frank Stella. Incidentally the couple also owned the largest private collection of Picassos in America. From 1968 to 1970, Eva taught at the School of Visual Arts, New York. In 1969, she was diagnosed with a brain tumour, and after three operations within a year, she died May 29, 1970. After her death, the Guggenheim Museum presented its first retrospective ever to a woman artist. At some stage we must confront the reasons for Eva’s use of latex and the question of why she devoted so much time to a medium she knew to be ephemeral. Some of her quotes could help to explain this and, at the same time, allowing conservators who are fighting a losing battle with some of her works, off the hook! She is certainly quoted as saying that she considered its instability an attribute. “And then the rubber only lasts a short time … I feel a little guilt when people want to buy it … I want to write them a letter saying its not going to last” “All order is ephemeral … chaos eats into order … yet it has its own order … if order could be chaos, chaos can be structured as non-chaos”. “Some of my work is falling apart … If and when I can repair it. If not, so what. They are not wasted. I went further in the work that followed”. Perhaps the answer lies in the remarks quoted earlier where she claimed that a woman lacked the conviction that she had the 'right' of achievement or that her achievements were worthy. She felt the need for “a fantastic strength” to prove this wrong and during a short career full of illness, instability and finally a brain tumour, she used her artworks to prove to herself that she could win. Permanence meant nothing. “Life doesn’t last, art doesn’t last, it doesn’t matter”. When the Ganz collection was sold by Christies in 1998, after Sally’s death, Eva’s “Unfinished, Untitled or Not Yet”, a 1966 sculpture of polyethylene, sand, paper and cotton, fetched a record price at Christie's of $2.2 million. Vinculum I (1969) became the artist's second most expensive work when it sold for $1.2 million. For those who would like to know more about Eva Hesse, her nearest works to London are in the Tate. From June to December 2002 there was a retrospective at San Fransisco MOMA, then at the Museum of Weisbaden and finally at Tate Modern. If you prefer literature, then “Eva Hesse” edited by Elizabeth Sussmann (ISBN 0-300-09168-0) with 320 pages and over 200 prints, mostly in colour, was published to accompany the exhibitions. |